Teacher’s Competence in Europe

In this report we connect the concept of competence with competence frameworks that provide tools to enhance professional teachers digital pedagogical competence. The concept of competence is separated, by paradigmatic difference, from the concept of competency, as competency refers to the potential of an individual as a whole (Mäkinen & Annala, 2010). The current educational paradigm in VET suggests that the domains of knowledge, skills and abilities (Nichols et al., 2017) describe the composition of individual competence. Competence can be seen also as an achievement acquired through training and development (McClelland, 1998; 1973). The European Reference Framework of Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (EU, 2007) describes “competence” as not only the required knowledge but also skills, attitudes and the ability to apply learning outcomes as is appropriate to the context (e.g., working life) (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Cedefop, 2014).

According to Eurydice’s recent report, “Teaching Careers in Europe” (2018), most European countries have defined a national framework to monitor teachers’ competences. These frameworks aim to identify the continuing training needs of teachers. More than one-third of nations with teacher competence frameworks use them for career guidance and CPD throughout teachers’ careers (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2018). According to the European digital framework (Kampylis et al., 2015), educational organisations should describe, maintain and evaluate their staff’s digital competence as well as that of their students.

Standardised Competence Frameworks for Educators

Digital pedagogy aims to foster creativity, play and problem solving in learning by coupling theory with practice and making with thinking (Spiro, 2013). This approach encourages participation, collaboration and public engagement and increases one’s critical understanding of digital settings. Professional teachers’ competence in digital pedagogy is seen as a combination of professional or substance specific, pedagogical and technological expertise (e.g., Guerrero, 2005; Koehler et al., 2013; Kullaslahti, 2011). Kullaslahti (2011) added teachers’ personal attributes to the list, that is, the continuous use of digital pedagogy and the development of one’s own work in cooperation with colleagues and the world of work. Context was also added to the description of competence based on the teacher’s role and tasks in his or her own organisation (Krumsvik, 2011, 2014; Kullaslahti, 2011; Lund et al., 2014; Prendes et al., 2011). The capacity to use technology is addressed as a transversal topic both for individual professional development and the development of any educational programme (Romero-Martín el al., 2017). Various digital pedagogical competence frameworks (Cabero-Almenara et al., 2020; Kools & Stoll, 2016; Tomczyk & Fedeli, 2021) have been developed to support teachers, educational organisations and legislators in delivering the effective and meaningful criterion-based professional development of different competences.

Information and Communications Technology Competency Framework for Teachers

Different initiatives to promote teachers’ professional development have been established based on evolving frameworks and guidelines. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO, 2011) Information and Communications Technology Competency Framework for Teachers (ICT-CFT) has provided the basis for current development work. Now, the emphasis has shifted from individual aspects and descriptions of technical know-how to the wider view of learning work communities and the multifaceted view on teachers’ competence in digital pedagogy. Brauer (2019, p. 21) explained that, “in addition to teachers, UNESCO’s ICT-CFT is intended to guide teacher trainers and staff undertaking learning reforms and executing professional development programs”. To put it simply, UNESCOs’ ICT-CFT outlines the competences required to teach effectively with ICT. The competence framework focuses on “the ICT skills needed to generate knowledge that enables reflective and creative problem solving for resourceful citizens who are in charge of their own lives and are active members of society” (Brauer, 2019, p. 21). The development of expertise at the upper levels of construction makes it possible for teachers to operate in regional, national and international networks.

Table 1 outlines UNESCO’s ICT-CFT as arranged to three successive stages of teachers’ professional development. The competence framework advances from understanding technology towards the development of learning organisations.

| Technology literacy | Knowledge deepening | Knowledge creation | |

| Understanding ICT in education | Policy awareness | Policy understanding | Policy innovation |

| Curriculum and Assessment | Basic knowledge | Knowledge application | Knowledge society skills |

| Pedagogy | Integrate technology | Complex problem solving | Self management |

| ICT | Basic Tools | Complex tools | Pervasive tools |

| Organization and administration | Standard classroom | Collaborative groups | Learning organizations |

| Teacher professional learning | Digital literacy | Manage and guide | Teacher as model learner |

The three successive stages of development aim to support teachers using ICT in enhancing students’ collaboration, creativity and problem solving. UNESCO (2011) described these three stages as follows:

The first is Technology Literacy, enabling students to use ICT in order to learn more efficiently. The second is Knowledge Deepening, enabling students to acquire in-depth knowledge of their school subjects and apply it to complex, real-world problems. The third is Knowledge Creation, enabling students, citizens and the workforce they become, to create the new knowledge required for more harmonious, fulfilling and prosperous societies. (p. 3.)

These successive stages of teachers’ professional development have been augmented at the European level by the Digital Competence Framework for Educators (DigCompEdu) proposing educator-specific digital competence (Redecker, 2017).

Digital Competence Framework for Educators

The extensive set of DigCompOrg framework has seven key elements and 15 sub-elements that are common to all educational sectors from early childhood to higher and adult education, including vocational education and training (Redecker, 2017). The framework aims to describe what it means to be a digitally competent educator. The guidelines propose an extensive set of competence descriptions, and the focus is not on technical skills. Digital learning technologies, in the context of DigCompOrg, constitute a key enabler for educational organisations, which can support their efforts to achieve their mission and vision for quality education. The DigCompOrg framework is designed to align with institutional and contextual requirements in different countries and is generic enough to apply to different educational settings allowing adaptation as technological possibilities evolve (Caena & Redecker, 2019). DigCompOrg is designed to focus mainly on the teaching, learning, assessment, and related learning support activities taking place in educational institutions.

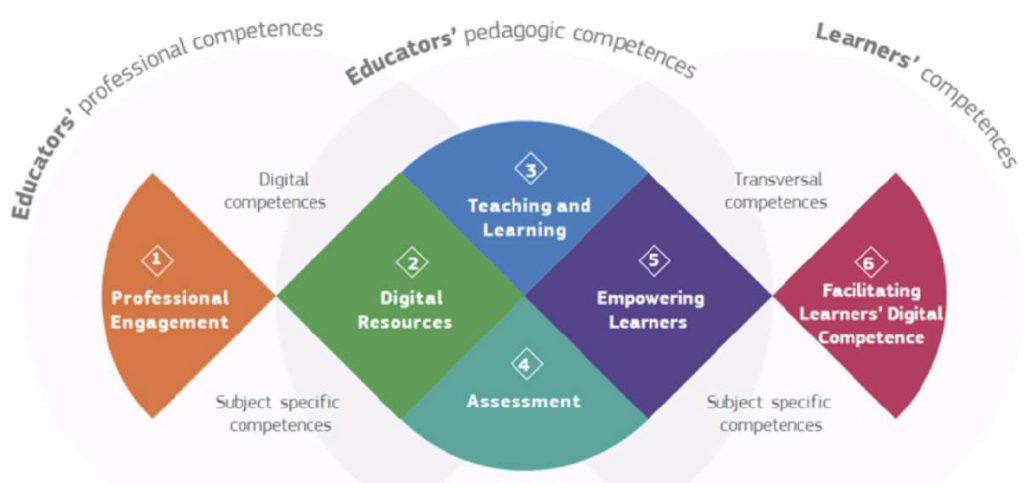

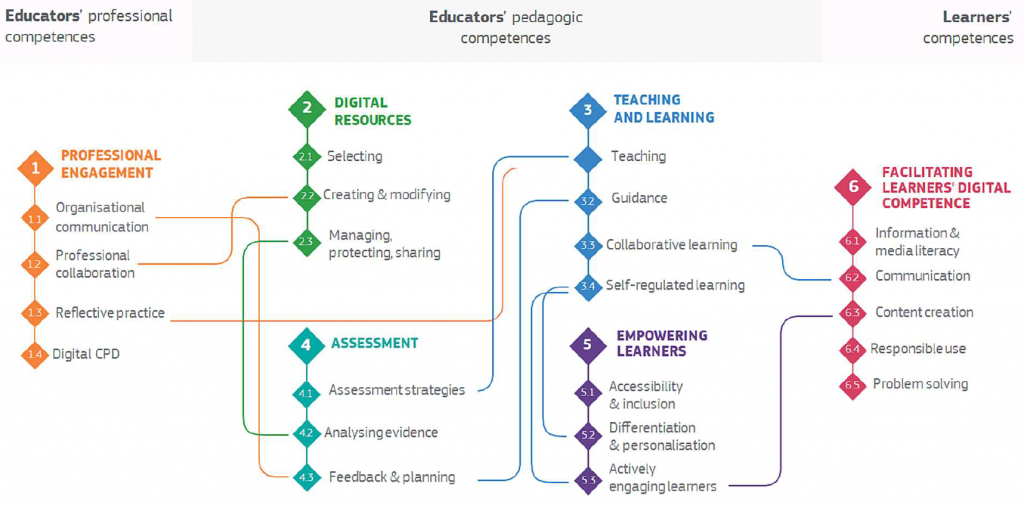

The European digital framework for teaching staff (DigCompEdu) is based on the competence descriptions of a digital citizen (DigComp), an educational organisation (DigCompOrg) and consumers (DigCompConsumers). The framework for DigCompOrg promotes effective learning in the digital era (Kampylis et al., 2015) for educational institutions and related organisations. The DigCompEdu framework describes the general digital competence required by teachers at all levels of education in detail. The DigComp framework can be used to develop relevant aspects of students’ digital competence. Figure 1 presents teachers’ desirable digital competence, as determined by DigCompEdu, including 22 different competences organised into six categories.

The six different areas focus on different aspects of educators’ competence. Areas 2-5 form the core of the DigCompEdu framework. They explain educators’ digital pedagogical competences describing competences educators need to foster efficient, inclusive and innovative teaching and learning strategies (Redecker, 2017). In Digital resources (area 2) focus is on planning teaching and learning: on sourcing, creating, and sharing digital resources. Teaching and learning (area 3) describes the implementation of teaching and learning process with the use of digital technologies. In Assessment (area 4) focus is on using digital technologies and strategies to enhance assessment; assessment strategies, analysing evidence, and feedback and planning. Empowering learners (area 5) contains a set of guiding principles relevant for competences specified in the areas 2, 3 and 4. Focus in that area is acknowledging the potential of digital technologies for learner-centred teaching and learning strategies, for example making learning materials accessible to all learners.

Professional engagement (area 1) is directed at the broader professional environment: using digital technologies for communication, collaboration, and professional development. Facilitating learners’ digital competence (area 6) describes specific pedagogical competencies that are required to facilitate students’ digital competence and enable them to use digital technologies creatively and responsibly. (Redecker, 2017.)

The framework aims to inform how digital technologies can be used to enhance and innovate education and training. DigCompEdu responds to Europe’s need to define digital competence specific to teachers and to harness the potential of digitalisation to improve several aspects of education. The scope is not entirely on educators’ pedagogical competences; it also allows for the need for professional development to be noted as well as the different intended competences of a learner.

Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge

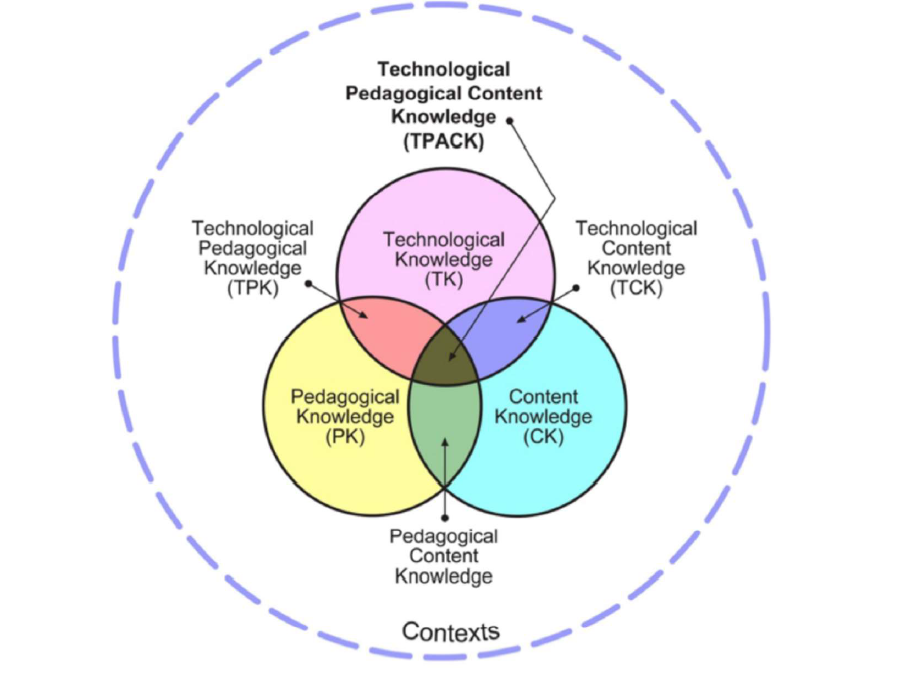

The approach of DigCompEdu may be considered multifaceted compared to the abundantly applied Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) model originating from the educational development that occurred in the U.S. in the ‘80s (Koehler & Mishra, 2009). Although the model is already ageing, it regularly emerges in discussions related to digital pedagogy. TPACK-model provides a clear structure to comprehend main characteristics of digital pedagogical development (Figure 3), although it does not reflect the emergent complexity of digital pedagogical competence needs in the educational sector.

In brief, the TPACK model is “a professional knowledge construct” (Koehler & Mishra, 2009, p. 66). As shown in Figure 2, “the content knowledge (CK) is teachers’ knowledge about the subject matter” (p. 63). Pedagogical knowledge represents “teachers’ deep knowledge about the processes and practices or methods of teaching and learning” (p. 64). The overlapping pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) determines a teacher’s pedagogical understanding in applying different approaches to teaching particular content. Finally, technological knowledge involves “open-ended interaction with technology” (p. 64). Koehler and Mishra (2009) concluded that, for technology to impact the practices and knowledge of teachers, “an understanding of the manner in which technology and content influence and constrain one another” (p. 65) is required. The technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) provides a comprehension of “how teaching and learning can change when particular technologies are used in particular ways” (p. 65). The approach should always be considered in the context of a specific discipline, keeping in mind the constraints and affordances of different technologies.

Applying technologies in teaching is complex, and new digital technologies face complicated challenges (Koehler & Mishra, 2009). Koehler and Mishra (2009) called for new ways to comprehend and accommodate this complexity as a precondition to succeed in educational technology integration, and TPACK, TPCK (technological pedagogical content knowledge) and the continuing value of Shulman’s original PCK model have been re-examined and reevaluated (cf. Abell, 2008; Berry et al., 2015). Abell (2008) concluded that, even after decades, “many questions remain within the PCK paradigm” (p. 1413). The researchers have not been able to determine how teachers generate and use PCK. Further, the knowledge transformation process has yet to be explained. In practice, PCK offers to inform how teaching different disciplines and subjects differs and how teaching affects students’ learning (Abell, 2008). Koehler and Mishra (2009) consider the cores of technology-enhanced teaching to be content, pedagogy and technology as well as the relations between these. Assessment itself is not mentioned as a core of technology-enhanced teaching. In DigCompEdu areas of focus assessment is seen as the core content of teacher’s competence (Redecker, 2017).

Changing a Paradigm

In general, the effects of digitalisation on teaching and scaffolding are difficult to encapsulate. A recent article by Tomczyk and Fedeli (2021) synthesises and compares such concepts as TPACK (Koehler & Mishra, 2009), DigCompEdu (Redecker, 2017) and UNESCO’s ICT-CFT (2011). Based on the review, Tomczyk and Fedeli (2021, n.p.) noted that:

- There is no one-size-fits-all way to measure digital literacy (DL) among teachers;

- The aforementioned theoretical frameworks mostly have clearly defined areas and levels of DL;

- Most of the concepts assume measurement through self-declaration, abandoning measurement through practical activities;

- All concepts clearly emphasise that DL cannot be separated from teaching processes;

- DL among teachers differs from DL among other professional groups, this being due to the specifics of the field;

- Differences in the formation of the most popular theoretical frameworks may be due to the richness of definitions of DL and the diversity of views on the process of the computerization of education;

- A common feature of the analysed frameworks is the integration of DL with methodological elements (content, methods, forms), and teacher and learner development; and

- The selected frameworks possess their own measurement tools.

Based on our studies, DigCompEdu can enable an understanding of how digitalisation transforms the perceptions of VET instructors’ competences and offers to inform and improve competence frameworks in terms of digitisation. However, there is no one-size-fits-all competence-based model for pre- and in-service training (Brauer, 2021) that would suit every educational organisation (Davies, 2017; Ipperciel and ElAtia, 2014; Ushatikova et al., 2016); indeed, there are significant differences between disciplines (Jerez et al., 2016). We suggest exploring different concepts and frameworks of the implementation of ICT in education. Nevertheless, clear articulation of VET teachers’, trainers’ and mentors’ competences is needed to reform educational practices to meet students’ individual interests and recognized working life needs. All approaches to competence-based CPD should adopt the coordinated policies both in design and implementation. Moreover, a mutual understanding of achieved competences should be based on public evidence (Brauer, 2021; Rhodes, 2012). The concerns of teaching staff regarding their own pedagogical competence must also be noted (de los Ríos-Carmenado et al., 2016; Jerez et al., 2016). A leap in competence development requires the expansion of educational provision of digital pedagogical in-service training (Brauer, 2021).

The current educational practices offer to inform teachers’ expectations towards the change in the educational paradigm (Brauer et al., 2022). In this report, we sought to understand the concept and effects of digitalisation through competence frameworks that corresponded to the concepts of this project in the context of the professional development of vocational teachers’ competences in the effective use of ICT in education. Keeping the different dimensions of digital pedagogy in mind, we will continue to look at the development of teachers’ professional competences in the digital era from different perspectives.

References

Abell, S. K. 2008. Twenty years later: Does pedagogical content knowledge remain a useful idea? International Journal of Science Education 30 (10), 1405–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690802187041

Berry, A., Friedrichsen, P. & Loughran, J. (EdS.) 2015. Re-examining Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Science Education. New York: Routledge.

Brauer, S. 2019. Digital Open Badge-Driven Learning -Competence-based Professional Development for Vocational Teachers. Doctoral dissertation. University of Lapland, Finland.

Brauer, S. 2021. Towards competence-oriented higher education: a systematic literature review of the different perspectives on successful exit profiles. Education + Training 63 (9), 1376–1390. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2020-0216

Brauer, S., Kettunen, J., Levy, A., Merenmies, J. & Kulmala, P. 2022. The Educational Paradigm Shift—Medical Teachers’ Experiences of Practices in Finland. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Cabero-Almenara, J., Romero-Tena, R. & Palacios-Rodríguez, A. 2020. Evaluation of Teacher Digital Competence Frameworks Through Expert Judgement: the Use of the Expert Competence Coefficient. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 9 (2), 275–293. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2020.7.578

Cedefop. 2014. Terminology of European education and training policy: a selection of 130 terms. Luxembourg: Publications Office. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications/4117

Davies, H. 2017. Competence-based curricula in the context of Bologna and EU higher education policy. Pharmacy: Journal of Pharmacy, Education and Practice 5 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5020017

de los Ríos-Carmenado, I., Sastre-Merino, S., Fernández Jiménez, C., Núñez del Río, M., Reyes Pozo, E. & García Arjona, N. 2016. Proposals for improving assessment systems in higher education: an approach from the model working with people. Journal of Technology and Science Education 6 (2), 104–120. https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.192

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. 2018. Teaching Careers in Europe: Access, Progression and Support. Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Union, EU. 2007. The key competences for lifelong learning – European reference framework. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/5719a044-b659-46de-b58b-606bc5b084c1

Guerrero, S.M. 2005. Teacher knowledge and new domain of expertise: pedagogical, technology knowledge. Journal Educational Computing Research 33 (3), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FBLQ7-AT6T-2X81-D3J9

Ipperciel, D. & ElAtia, S. 2014. Assessing graduate attributes: building a criteria-based competency model”. International Journal of Higher Education 3 (3), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v3n3p27

Jerez, O., Valenzuela, L., Pizarro, V., Hasbun, B., Valenzuela, G. & Cesar O. 2016. Evaluation criteria for competency-based syllabi: a Chilean case study applying mixed methods. Teachers and Teaching 22 (4), 519–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1082728

Kampylis, P., Punie, Y. & Devine, J. 2015. Promoting Effective Digital-Age Learning. A European Framework for Digitally-Competent Educational Organisations. EUR 27599EN. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2791/54070

Koehler, M. J. & Mishra, P. 2009. What is technological pedagogical content knowledge? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 9 (1), 60–70.

Koehler, M.J., Mishra, P. & Cain W. 2013. What is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education 193 (3), 13–19.

Kools, M. & Stoll, L. 2016. What Makes a School a Learning Organisation? OECD Education Working Papers, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlwm62b3bvh-en

Kullaslahti, J. 2011. Ammattikorkeakoulun verkko-opettajan kompetenssi ja kehittyminen. [Online-teachers’ competence and development in universities of applied sciences]. Academic dissertation. Tampere University.

Krumsvik, R. J. 2011. Digital competence in Norwegian teacher education and schools. Högre utbildning 1 (1), 39–51.

Krumsvik, R. J. 2014. Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of Education Research 58 (3), 269–280.

Lund, A., Furberg, A., Bakken, J. & Engelien K.L. 2014. What does professional Digital Competence Mean in Teacher Education? Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 9 (4), 281–299.

Prendes, P., Castañeda, L. & Gutiérrez, I. 2011. University teachers ICT competence: evaluation indicators based on a pedagogical model. Educação, Formação & Tecnologias, extra, Abril, 20–27. https://www.academia.edu/31000139/University_teachers_ICT_competence_evaluation_indicators_based_on_a_pedagogical_model

McClelland, D.C. 1973. Testing for competence rather than for ‘intelligence’. American Psychologist 28, 423–447.

McClelland, D.C. 1998. Identifying competencies with behavioural-event interviews. Psychological Science 9 (5), 331–339.

Mäkinen, M. & Annala, J. 2010. Osaamisperustaisen opetussuunnitelman monet merkitykset korkeakoulutuksessa [Various aspects of the competence-based curriculum in higher education]. Kasvatus & Aika 4 (4), 41–61.

Nichols, P. D., Kobrin, J. L., Lai, E. & Koepfler, J. 2017. The role of theories of learning and cognition in assessment design and development. In A. A Rupp & J. P. Leighton (Eds.) The handbook of cognition and assessment: Frameworks, methodologies, and applications. Chichester, West Sussex, England: Wiley Blackwell.

Redecker, C. 2017. European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu. In Y. Punie (ed.) EUR 28775 EN. JRC107466. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/european-framework-digitalcompetence-educators-digcompedu

Rhodes, T. L. 2012. Show me the learning: Value, accreditation, and the quality of the degree. Planning for Higher Education 40 (3), 36–42.

Romero-Martín, R., Castejón-Oliva, F.-J., López-Pastor, V.-M. & Fraile-Aranda, A. 2017. Formative assessment, communication skills and ICT in Initial teacher education. Comunicar 25, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.3916/c52-2017-07

Spiro, L. 2013. Defining Digital Pedagogy. [PowerPoint slides] WordPress. https://digitalscholarship.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/gettysburgintrodigitalpedagogyfinal.pdf

Tomczyk, Ł. & Fedeli, L. 2021. Digital Literacy among Teachers – Mapping Theoretical Frameworks: TPACK, DigCompEdu, UNESCO, NETS-T, DigiLit Leicester. Proceedings of the 38th International

Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), 23–24 November 2021, Seville, Spain. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356672873_Digital_Literacy_among_Teachers_-Mapping_Theoretical_Frameworks_TPACK_DigCompEdu_UNESCO_NETS-T_DigiLit_Leicester

UNESCO. 2011. UNESCO ICT Competency Framework for Teachers. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002134/213475e.pdf

Ushatikova, I. Rakhmanova, A., Kireev, V., Chernykh, A. & Ivanov, M. 2016. Pedagogical bases of formation of key information technology competencies polytechnic institute graduates. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6(2S), n.p.

Vastaa

Sinun täytyy kirjautua sisään kommentoidaksesi.